Published: Feb 25, 2024 by Yu-Wen (Weny)

What is interoperability?

In medical devices, “interoperable medical devices refer to the ability to exchange and use information through an electronic interface with another medical/non-medical product, system, or device. Interoperable medical devices can be involved in simple unidirectional data transmission to another device or product or in more complex interactions, such as exerting command and control over one or more medical devices. Interoperable medical devices can also be part of a complex system containing multiple medical devices.” [The US FDA, Design Considerations and Pre-market Submission Recommendations for Interoperable Medical Device, issued on September 6, 2017]. For example, a blood glucose meter that can send data to a smartphone app, an x-ray that can communicate with a picture archiving and communication system, or a ventilator that can adjust its settings based on the patient’s vital signs are all examples of interoperable medical devices.

From a medical device manufacturer perspective, if you take a look at the HIMSS interoperability guidance, you will find that the first three levels may be applicable to your devices:

| Level | Description | Application in Medical Devices |

|---|---|---|

| Foundational (Level 1) | Establishes the inter-connectivity requirements needed for one system or application to securely communicate data to and receive data from another | Data exchange between systems, no further interpretation (e.g., a simple upload to the drive) |

| Structural (Level 2) | Defines the format, syntax and organization of data exchange including at the data field level for interpretation | Data exchange in XML or JSON (specific format or structure), so that the receiver can interpret and use the data |

| Semantic (Level 3) | Provides for common underlying models and codification of the data including the use of data elements with standardized definitions from publicly available value sets and coding vocabularies, providing shared understanding and meaning to the user. | Standards include Vocabulary/Terminology Standards, Content Standards, Transport Standards, Privacy and Security Standards, and Identifier Standards. |

| Organizational (Level 4) | Includes governance, policy, social, legal, and organizational considerations to facilitate the secure, seamless, and timely communication and use of data within and between organizations, entities, and individuals. These components enable shared consent, trust, and integrated end-user processes and workflows. | It Goes beyond the technical aspects, which are out of the scope of this discussion. |

Interoperability can offer many benefits for the safety, effectiveness, and efficiency of medical devices and the quality of care and patient outcomes. A good interoperability design will cover the aspects of

- clinical usage

- safety

- cybersecurity

- Usability

What are the best practices to assess your interoperability capabilities?

When you want to evaluate and improve their interoperability capabilities, below is a suggested systematic and comprehensive approach for your reference (and you will find it highly overlaps with the cybersecurity practices):

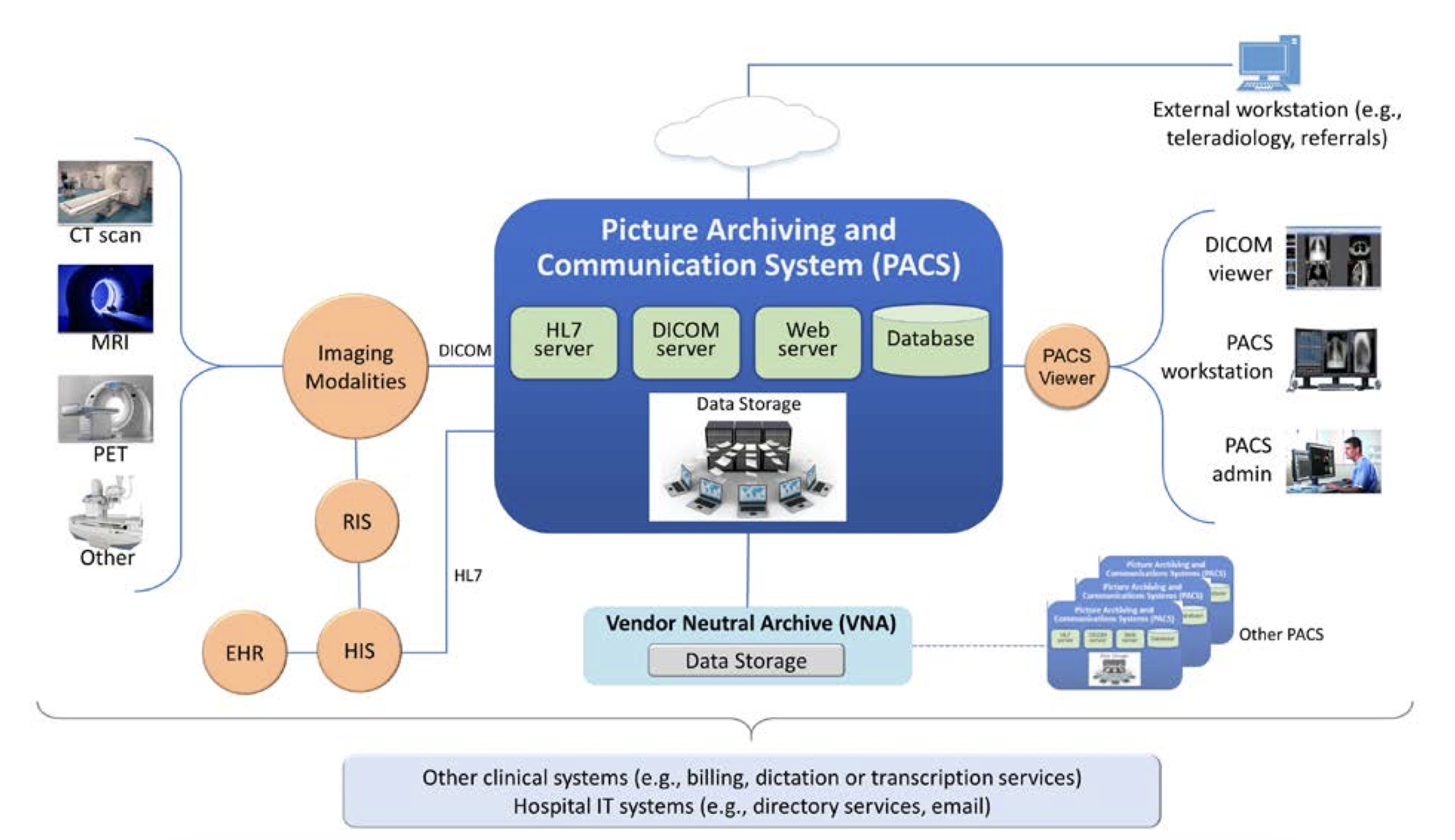

- Global system view: As part of the design inputs and pre-threat modeling practices, draw a global system view to consider the whole system that your device is part of, including the other devices, systems, users, and environments that their device interacts with. I always like the example the NIST security PACS publication gave, which shows a clear global system view with other devices.

- Design inputs: Design inputs: Consider what needs to be exchanged, the interface, the users, communication format, rate, and transmission method, limitations (what the user should not do), contraindications, precautions, warnings…etc. (FDA guidance device description section).

- Risk assessment and cybersecurity assessment: two levels of controls at least, the communication protocol you use (e.g., Bluetooth, Bluetooth Low Energy, network protocols) and the checks within your systems (fault tolerant behavior, boundary conditions, and fail safe behavior such as how the device handles delays, corrupted data, data provided in the wrong format, unsynchronized or time mismatched data, and any other issues with the reception and transmission of data)

- Security design objectives are still applicable: Authenticity, which includes integrity; Authorization; Availability; Confidentiality; and Secure and timely updatability and patchability.

- Using Interoperability Standards is always preferred, if available and applicable.

- Verification and validation

FAQ

There is no way I can do V&V on all the appliable interoperable devices. What should I do?

If you refer to a common standard, you should be able to have a statement that this is the standard you are compliant with. For example, it is very common for radiology device manufacturers to have the DICOM statement.

If what you need is more than a statement, you may be able to design a formalized verification protocol, ensuring that all applicable interoperability requirements are covered, and this verification protocol will be used as part of the installation verification activities. You should have some representative devices used as part of your process verification in the production stage. Of course, having a presubmission meeting is always the most effective way to know regulatory authorities’ expectations.

What if, in my field, there are no common standards applicable?

If there is no standard format in your field, you may need to communicate with the regulatory authorities beforehand to ensure you know their expectations. You may propose using specification (labeling) in addition to the testing protocol you have validated if you can justify the safety and effectiveness/performance.

In some cases, you may only be able to claim the compatible devices you have the interoperability testing. For some product types, the regulatory bodies will ask you to specify the device and model that your devices are compatible with in your IFU.

What are the differences between an interoperable device and an off-the-shelf (OTS)?

I’ve been asked this interesting question more than once.

| Feature | OTS (Off-the-Shelf) Software | Interoperable Devices |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | a generally available software component, used by a medical device manufacturer for which the manufacturer cannot claim complete software life cycle control (e.g., operating system, printer/display libraries) | (devices) have the ability to exchange and use information through an electronic interface with another medical/non- medical product, system, or device. |

| Location | Within your product (may or may not be within the device function) | Out of your product boundary but you may mention it in your intended use/use cases |

| QMS controls | Supplier, configuration management, SBOM…etc. | You don’t really have control over it. The focus will be on the voluntary standards (e.g., for data exchange) or specification (e.g., released API specifications) |

| Corresponding FDA guidnace | Off-The-Shelf Software Use in Medical Devices | Design Considerations and Pre-market Submission Recommendations for Interoperable Medical Devices |

| Risk assessment and V&V | Yes | Yes |

| Labelling requirements | Yes | Yes |

| Other | Based on the use cases, may be applicable in the Usability testing |